Archive for the ‘Texas’ Category

The Alamo Does Tom Blog

October 1, 2013Lone Star Losers

December 21, 2010More than most kinds of nostalgia, Texan nostalgia is absurdly easy to overdo. That helps to explain why Eagle Pennell’s first two feature films—The Whole Shootin’ Match and Last Night at the Alamo—are such special things. Both movies are intricately, almost embarrassingly, familiar with certain Texan types and attitudes, yet manage to explore them without either sentimentalizing or condescending to them. To this pair of eyes at least, Pennell’s movies, even with their rough edges (and some of those edges are really rough), present a truer picture of Texas than all of the Hollywood colossi striding through Giant, the dirt-kicking mumblefucks of Tender Mercies, or the upscale hot-house symbols and tropes swarming like locusts through Hud, Lone Star, and The Last Picture Show.

I first saw Last Night at the Alamo on television around 1985. It definitely stood out from the other cable fare of the time, if only for the humble place it occupied in the world. Its miniscule arena extends no further than the premises of a mildewed Houston dive—“The Alamo”—on the night before it’s to be bulldozed and replaced by condos; its action consists of about a dozen of the bar’s regulars acting out their nightly rituals one last time before losing what for most of them is their real home. In places the movie feels like an artistic commando raid, rescuing characters—a henpecked husband, a perpetually pissed-off redneck kid—who are usually confined to the background of movies, and dragging them front and center where we can take a good, long look at them.

The movie’s brazenly foul-mouthed dialogue also made it memorable, for Last Night at the Alamo has a case of potty-mouth like few other movies do; Deadwood by comparison sounds like the Gettysburg Address. One character in particular—the almost metaphysically miserable Claude, played by Lou Perryman—delivers a graduate seminar in framing life’s dilemmas using only four-letter words. Yet for all its rambunctiousness, Last Night at the Alamo remains focused, mostly on the travails of “Cowboy” (Sonny Carl Davis), the bar’s most celebrated regular. Cowboy is a balding, sawed-off John Wayne wannabe who gets through life by posing as a grinning, strutting good-time-charlie. A little man revered by the other barflies only because they themselves are so small, Cowboy claims to have a secret plan to save The Alamo, and it comes as no surprise when it works about as well as Nixon’s secret plan to get us out of Vietnam. (Because of their relative sizes Perryman and Davis resemble a redneck Mutt and Jeff, but in terms of what they mean to Pennell’s movies it’s more useful to think of William Demarest and Preston Sturges or Elliot Gould and Robert Altman—as living, breathing manifestations of the filmmaker’s personality.)

Last Night at the Alamo’s finest accomplishment is recognizing its characters as the misogynistic alcoholic losers they are without ever giving up on them as human beings. Celebrations of the pathetic are rare enough in art, but they’re nearly unheard of in contemporary America, where normal human concerns about status and self-esteem have blossomed into full-blown psychotic obsessions, and people act as if spending time with even fictional failures brings bad juju. Yet Pennell and his co-scenarist Kim Henkel don’t bother giving Cowboy & Co. any synthetic little touches to redeem them or make them “worthy” of our interest. It’s simply assumed that their very existence is reason enough to care about them—a notion which, if it’s good enough for democracy, ought to do for a movie.

Pennell’s 1978 ode to scrapers and battlers The Whole Shootin’ Match is even purer than Alamo. It follows two Austin lowlifes, Loyd and Frank (Perryman and Davis again), who fill their days working as common laborers and dreaming up fanciful get-rich-quick schemes. Again Pennell (this time sharing writing duties with Lin Sutherland) doesn’t shy away from his heroes’ darker patches—at one point Frank, his manhood stung by his cousin’s flirting with his wife, mindlessly takes a belt to his young son—yet the movie’s overriding tone is affectionate and understanding. When one of their schemes seems certain of a big-time payout, Frank treats himself to a leisure suit and cowboy hat, and his shopping spree is a delight to watch even though we know he’s setting himself up for a fall. The last scene, in which the two old friends make a long quixotic trek across the Hill Country in search of Spanish treasure and wind up making some peace with their jimmy-rigged lives, is memorable both for its easygoing pace and the physically convincing vibe of a long day spent outdoors. (Robert Redford has often cited Shootin’ Match—the archetypal regional, independently financed production—as a primary inspiration for the Sundance Film Festival.)

Pennell made three more movies after Last Night at the Alamo, all of them unavailable on home video, and all of them reputedly awful. After his early successes he suffered a long, sad decline, eventually drinking himself to death in Houston in 2002. Earlier this year Watchmaker Films released The Whole Shootin’ Match on DVD, along with a documentary by Pennell’s nephew which, in the course of tracing his rise and fall, touches on filmmaking, Austin in the ’70s, and terminal alcoholism—and it’s superb on every count. (Last Night at the Alamo has never made it to DVD but remains available via used VHS tapes, occasional cable broadcasts and YouTube.) Perryman, Davis and their splendid co-star Doris Hargrave, about whom I haven’t said anywhere near enough, provided a commentary track for Shootin’ Match that’s colorful and informative, even if it doesn’t reach the uproarious heights of The A.V. Club’s fabled 2008 interview with the two men. In an agonizing postscript, Lou Perryman was murdered in his Austin home in April 2009. It remains a mystery why he and Pennell had to meet ends so much harsher than anything they wished on their characters.

Dog Canyon 2009

“The friendliest people and the prettiest women you’ve ever seen”

October 6, 2010I had nothing short of a goddam blast in Austin—four or five days hanging out with a variety of terrific people, and enough of a good time that I’m wondering how much longer I’m going to last in San Francisco. I still love a lot of things here, no doubt about that, but Austin completely whips S.F.’s ass on a couple of crucial fronts. Mainly, the folks there are so welcoming and unpompous that it was easy to drop my own bullshit—all those impulses honed by spending too much time around hipsters and the vagrant, shaky egos on the Internet. Anyway, right now I’m caught between catching up on my work and falling fast asleep at my desk—I’ll have to write more later.

Reach for the Sky

August 20, 2010It was four or five obsessions ago—before film noir, before the Iraq War, before Enron and the Italian neorealists and vegetarian cooking the Army-McCarthy hearings—that I really plunged into the gunmen of the Old West. It lasted a while, a year or two in any case, and in that time I bored certain people silly (Gary, Kathy, Cay—are you still out there?) with the exploits of such forgotten men as John Selman, King Fisher, and Outlaw Bass. For instance, there was the handsome train robber Tom “Black Jack” Ketchum,

who caused some excitement when his head popped off during his hanging,

and “Deacon” Jim Miller, the religious nut and hired killer who asked permission to keep his hat on before getting strung up in an Oklahoma barn,

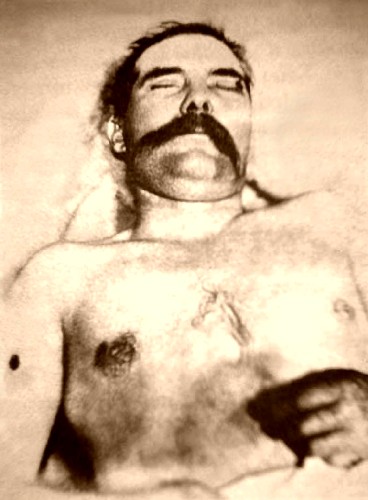

and Henry Brown, the popular but poorly paid marshal of Caldwell, Kansas, who decided to improve his lot in life by robbing the bank one town over from his own. It was a bad move: a couple of citizens were killed in the robbery, then Brown and his friends managed to trap themselves in a box canyon that was filling up with rainwater. They surrendered and spent the day in the Medicine Lodge lockup, waiting for the mob to reach its boiling point; while not posing for photographs at gunpoint, Brown used the time to write a letter to his wife which ended: “It was all for you. I did not think this would happen.” When the mob finally came that night, Brown made a break for it and was shot down in the street. That’s Henry, second from the left there, in shackles:

Some of the most famous gunmen were so thickly embroiled in the currents of history they seem like frontier Forrest Gumps, yet one can’t say much about them as people. These were far from self-actualized men, to put it mildly, and they had no say in how others represented them. Some of them come across as sociopaths pure and simple, others as workingmen carrying capitalism to its logical end, but in the main their personalities don’t communicate across the ages in any illuminating way, leaving us only with their violent, often nugatory experiences. Those experiences, draped as they were in law-breaking and immorality, were a tangled web to begin with, and any remaining hope of clarity was dimmed when generations of dime novelists, journalists, and slipshod historians took to heart the words of the too-slick newspaper editor in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Every field is open to information abuse, but the Old West was left to the amateurs for so long that peer reviews and other reality-checks couldn’t obtain a toehold for decades, allowing writer after writer, for generation after generation, to repeat “the legend”—the myths, tiresome the second time you read them, that Billy the Kid shot a man for every one of his 21 years, that Hardin once shot a man for snoring. Indeed, “the legend” was regurgitated so many times that the writer-bibliographer Ramon Adams felt moved to compile Burs Under the Saddle, a virtual encyclopedia of errata which painstakingly corrects, one by one, the outright myths and half-truths peppering Western histories. Beyond the weekend warriors, the field has also seen its share of warlords and empire builders, most notably the belligerent and quite possibly insane Glenn G. Boyer, whose inexplicable mindgames have hindered serious researchers for years. Nor do publishers, especially in the academic world, offer much help when they saddle their offerings with presentations trivializing their own subject matter. When the University of Oklahoma Press reissued John Wesley Hardin’s autobiography for the first time in decades, this is what it looked like:

Likewise, Joseph G. Rosa’s indispensable pictorial biography The West of Wild Bill Hickok is available only in a cheaply produced edition even though Hickok led a life richer than Picasso’s, and the man himself, an incorrigible camera hound, possessed one of the great modern gazes in 19th Century photographs.

Despite all this, certain potent snapshots still jump out from the literature that is reliable: a disconsolate Hickok sitting on his bed, surrounded by firearms, as a half-dressed prostitute putters about his room; or Henry Brown’s vest catching fire from a pistol flash and going up in flames as he ran down the street during that escape attempt. These luminous, ephemeral glimpses have no more substance than heat lightning, and they’re no help at all to, say, the grad student writing a thesis on the economics of mining towns. Anecdotal history like this doesn’t leave much more than a feeling, but it’s a feeling that’s tangled up with the texture of some rugged lives once lived, a constant shifting between the gridpoints on a wilderness, an easy familiarity with violence, and the unmistakably American flavor of all these things; if nothing else it injects some small dose of grit and authenticity into an age of designer-ripped jeans and Lady Gaga.

John Wesley Hardin, for instance, came out of the East Texas hills, the son of a Methodist circuit rider (hence the name), and his early reputation as a mankiller was based on run-ins he had with freed slaves, Union soldiers, and the hated (by Democrats and ex-Confederates) State Police. Getting himself into scrape after scrape, he was a fugitive long before he was 20; in the Taylor-Sutton feud he shotgunned a man on the deck of a riverboat even though the fellow was known to be fleeing the territory; when he subsequently murdered a deputy and lit out again, a furious mob strung up his brother.

The Texas Rangers caught up with him on a train outside Pensacola, knocked him out, and renditioned his ass back to Texas, where he was given a 25-to-life prison term. In Huntsville he taught Sunday school—par for the course for celebrity felons today, but Hardin seemed to believe his own sermons, and he went one step further and began studying law. He served 20 years before he was pardoned in 1894, and the Texas of his youth was fading away fast. He passed the Bar but few people wanted to pay John Wesley Hardin for his legal advice. He married a 15 year old girl who fled on their wedding night and refused to discuss him ever again. The children from his first marriage, grown now, were strangers to him. He moved to El Paso and hung out a shingle.

There he began work on his autobiography, a book short on insight but long on detail, with names and dates supplied for almost every killing, some 30 or 40 in all. He distributed autographed playing cards drilled by bullet holes—keepsakes which are traded to this day. But things continued to slide downhill for him: not enough clients, a messy affair with the wife of one of the few clients he did possess, a card game that so pissed him off he scooped up the pot and walked out the door, silently daring anyone to object. The local newspaper, hearing of this, began a drumbeat: the day of the gunman was over. It was just a matter of when. There was one final dispute, one final exchange of charges and countercharges, this time with a degenerate constable, and on August 19, 1895—115 years ago yesterday—Hardin was playing dice in the Acme Saloon when John Selman stepped up and shot him in the back of the head.

Now, not even with a gun to my head could I tell you why I find these details irresistible. The fact is, I just do…

"Get your hat and your bottle there. You don't have to do nothin'–just come along with me."

September 10, 2009Anyone who hasn’t seen Eagle Pennell’s The Whole Shootin’ Match ought to consider ordering it immediately—for a low-rent DIY project I’ll take it over Killer of Sheep any day of the week. Just if you get it from Netflix, make sure you also get the disc that has the documentary The King of Texas on it. It covers Pennell’s life in just the right amount of detail, but it also stretches out to include Texas, filmmaking, Austin in the ’70s, friendship, and life as lived in close proximity to a terminal alcoholic, and it’s superb on every count. Interviews with all the principals in Pennell’s life (if it wasn’t before, Lou Perry’s murder is unbearable now) plus variously sized visits with Bud Shrake, Willie Nelson, Richard Linklater and many other colorful Austinites.

And here I was thinking no one knew how to do melancholy any more. Man…

When accountability still meant something

May 10, 2007I spent this afternoon watching the last half of something I forgot I even had, the 250-minute documentary about Nixon’s second term simply called Watergate that BBC and The Discovery Channel put together about 15 years ago. I have about five documentaries and specials about the mess but this one is the mother of them all. That’s partly because it isn’t fixated on The Washington Post’s role the way the others are—Woodward and Bernstein make an appearance alright, but they’re onscreen just a tad longer than Tony Ulasewicz, and they get a helluva lot less face-time than Dean or McCord or that bow-tied dandy known as Archibald Cox. Another thing that makes it great is that the filmmakers somehow put all the subjects at their ease, with Haldeman and Ehrlichman in particular showing hitherto hidden human faces. Nixon himself is present only in the form of generous excerpts from the David Frost interview in ’77, and when describing the meeting in which he fired Haldeman, Nixon describes his old chief of staff, spitting the words out as they come to him, “not as some Germanic…Nazi…stormtrooper,” which does pretty much nail the public’s perception of the guy, but as a “decent public servant.” That last phrase might be stretching a point but Haldeman comes off well. With his hair grown out a tad and wearing a plaid shirt, khaki pants, and a pair of half-glasses, he comes across like an uncle at his favorite fishing lodge. And he’s not alone. Ehrlichman, Liddy, Dean, Magruder, Colson, Mardian, Porter—damn near all of them—speak out with a surprising openness and lack of rancor, and the way their interviews are woven together makes us feel for once that everyone’s telling the truth.

There are exceptions. John Mitchell, who died years ago, isn’t on-hand, of course, but you get the feeling that even if he was he wouldn’t have been interested in opening up to a film-crew for a documentary narrated by Dan Schorr. He’s the one who bluntly told the Ervin Committee that he considered Nixon’s re-election so important because of “what the other side was putting up” that he would’ve done anything to accomplish it, and he’s also the only one who failed to see the humor in his exchange with Sam Dash. When Dash asked Mitchell why he hadn’t thrown Liddy out of his office while Liddy was describing one of his hare-brained (and highly illegal) schemes, Mitchell, pipe in hand, evenly replied, “In retrospect, I wish I hadn’t just thrown him out of my office, but that I’d thrown him out of the window.” With a professional’s timing Dash let the answer hang in the air before prefacing his next question with, “Seeing as how you did neither…” As the caucus room rang out with spontaneous guffaws, the camera zoomed in on Mitchell who, judging by his expression, looked as if he were trying to decide whether it would be more fun to kill Dash by roasting him on a spit or throttling him with his bare hands.

Still, the man who comes off the ugliest isn’t named Mitchell or Haig or even Richard Milhouse Nixon. It’s E. Howard Hunt, the reputed “spymaster” who did us all a favor by dying and going to Hell just a few short weeks ago. Hunt, it will be recalled, led the planning for the break-in along with his co-mastermind Gordon Liddy, and it was he who began squeezing his former bosses for hush money after his arrest. Hunt, too, appears in contemporary interviews, but where even the likes of Colson, Magruder, and Ehrlichman mellowed with age, and managed to recognize the tawdriness in their own souls somewhere along the way, Hunt gazes into the camera as one might regard a bottle of cyanide as he talks about the “considerations” he felt were due him. It’s a disgusting, even disquieting, performance.

You Can Get Anything You Want…

March 4, 2007In the couple years surrounding our last year of high-school all we did was drive around town every night, getting stoned and talking and finding (usually) innocuous ways of getting into trouble. Since the “getting stoned” part was de rigeur, we wound up frequenting, on a more or less rotating basis, a handful of households that usually had some stash lying around. John and Suzy Joyce*, along with their three young kids, made up not just one of the most welcoming of these households, but easily the most comfortable one. They owned a house in Houston’s Montrose District, a rambling two-story affair that reeked of comfort and roots, and we wound up there at least once a week. It was my sister, Polly, who introduced me to the Joyces (God knows where she met them), but since she was a couple years older than I was chronologically (and a lifetime older than me in terms of maturity) she ran with her own crowd of friends. (There was a period of time where Polly and I ran into each other more at the Joyces’ than we did in our own home.) But usually it was me and Glenn and Dennis, or some subset thereof, who’d show up unannounced on their doorstep. John and Suzy were in their mid to late 30s, almost a generation away from us, but their open-door policy dictated taking in everyone, both the river of friends that flowed through the place as well as these scrounging little long-haired rats who came to scarf down the remnants of that night’s pot of chili and then get high on their pot or hash and zombie out on the livingroom floor while the stereo blared away. Suzy had a frizzed-out mop of hair that tentacled out in every direction, and tended to wear tent-like dresses stamped with African prints that pooled out around her legs when she put her feet up on the couch, while John (who supported the family by working as an architect) looked like George Carlin in his glory days, only with a slow, considered, ruminative way of talking—a trait I initially took as a sign of maturity and wisdom.

The kids were young enough that they were always in bed by 9 or 10, leaving us free to stay up all hours of the night, listening to music and talking, talking, talking. In the early years a lot of it was about the war and Nixon, but in time the conversation revolved more and more around books and movies. John and Suzy could talk about that shit, too, though Suzy was the more knowing and curious one of the two: when Glenn and I came in raving one night about some movie we’d just seen called McCabe & Mrs. Miller, she got up without a word and put on The Songs of Leonard Cohen while we sat there with our mouths open. In high school my bond with Glenn was galvanized by “Howl,” Desolation Angels, and some of the other Beat tracts, but eventually we fell under the baleful influence of the Modernists—a development that doubtless elevated the level of our conversation, but which also hardened us, and made us haughty and impatient with lesser work. Sometimes we were making a legitimate point, but more often we were just being a pain in the ass. The only thing is that the air was full of “lesser work” at the time. It was the age of The Eagles and of the disaster-movie cycle and of Jonathan Livingston Seagull; the cultural landscape was so overloaded with crap it was possible to overlook the fact that American cinema was enjoying a renaissance.

All of this only served to irritate us that much more. I don’t even remember what movie it was now, but one night John Joyce offered up the earth-shaking opinion that such-and-such a film may not have constituted a crime against humanity, and Glenn and I went to work on him. What-about-this, and What-about-that, we kept asking him, growing a little more unsparing with the adjectives we were throwing out with every swing of our whipsaw. We thought we were just having another conversation, so we were surprised when Suzy suddenly got up, crying, and ran out of the room. Somehow that night ended with Glenn and me sitting up with her in the kitchen while she explained to us, decidedly not in so many words, that John, lovely man that he was, just wasn’t very bright. “He tries so hard,” Suzy said, and I think now she was asking us not to lean on him like that again. What it all meant was that John’s deliberate way of talking wasn’t wisdom at all—it was just simple insecurity about saying the wrong damn thing. Listening to Suzy I had the same feeling you get the first time you see your parents fail at something and you realize they’re just doofuses, too, a comparison all the more fitting because it was the first chink of any kind I’d ever seen in the armor of their marriage.

A little time passed, both Glenn and Dennis moved away, I got a girlfriend and a life of my own, and I didn’t see the Joyces anymore. Then came the news from Polly that Suzy and John had separated and were getting divorced—an idea that would’ve upended the world had it come a couple years earlier—and that John was drinking too much. Suzy kept the Montrose house for a couple more years before moving her brood to Colorado, where Polly, in her peripatetic journeys around the Southwest, would often see her.

Finally one night around ’78 or so, I ran into John in Cactus Records. He looked like he was 65 and he was completely shit-faced, stumbling around the aisles and hanging onto the bins to stay upright. I wasn’t in a good place either then—a horrible breakup had left me a dilapidated, weak-willed mess—so I took John up on his offer to have a drink at his house. His “house,” I call it—actually it was a dingy one-bedroom apartment, nearly bereft of furniture and a long ways down from the warm paisleys and throw-pillows of his old home. We sat at a bare kitchen table, and he kept pouring so I kept drinking, especially since he was eager to have someone else who’d recently been dumped beside him. He launched into a couple anti-Suzy tirades that he almost immediately took back, but then out of the blue he remembered that night and he turned his guns on me. Whatever sketchy camaraderie we’d developed in the previous hour evaporated as he started telling me what superior sniveling snots Glenn and I had been, and on he went until he was blaming the breakup of his marriage on a couple of pretentious twenty-somethings. I sat and listened to it for a while before I finally bailed, and when he called stone-cold sober a week later to see if I wanted to get together for a drink, I begged off. I never saw him again.

Or Suzy either, for that matter, though Polly’s relayed the news about her over the years. Those kids we used to shoo upstairs are pushing 40 now, and Suzy somehow landed on a ranch of her own, and nobody knew for sure where John was. Then, on this last Wednesday, Polly emailed me to say that Suzy had gotten intestinal cancer that jumped down her hip bone and into her leg, before killing her a couple of weeks ago. The news hit with only a distant thud, but I didn’t have to think very hard before I remembered all those good nights we had, along with those couple of bad ones. Any lessons I might’ve learned from knowing the Joyces I either learned or didn’t learn 30 years ago, and there’s nothing else to say about it now except thanks for the weed and the chili, Suzy. For the most part I had a really good time.

* – an alias

A Few Words from Our Sponsor

March 4, 2007Thanks to my friend Chris Lanier, I wound up appearing on Steve Lambert’s show on UC Davis’ radio station a couple weeks back. (Chris can also be heard on the program, recounting with Homeric splendor the mighty Battle of the Pine Needles.) Steve’s ostensible theme was “Fist Fights and Violence” but that didn’t stop me from saddling up some of my pet hobbyhorses—Peckinpah, The Sopranos, the corruption of feminism—and riding them into the ground, thus boring an audience much wider than my close circle of friends for a change. You can hear the show on Steve’s website by scrolling down to Episode 10 and clicking on the sound bar. There aren’t any earth-shaking insights, but I did I get to tell a couple of my circus stories (though I unconscionably neglected to give shout-outs to the two horses I handled, Pancho and Frosty), and Steve did a really nice job with the editing. That post about Dority’s fistfight also got cannibalized for a contribution to The High Hat a couple of issues ago. That issue was intended (in part) as a tribute to Robert Altman (who died unexpectedly about 24 hours after it came online, making me think that a special issue about Dick Cheney might be in order), and also includes my take on California Split—still a piece of relevant (and hilarious) filmmaking 30+ years after the fact.

Dem Bones, Dem Bones

October 18, 2005A couple days ago a local big-time criminal defense attorney found his wife’s body in their home – she had the ol’ multiple blunt trauma to the head thing going – and the TV media here, smelling another O.J./Laci epic in the offing, have gone absolutely nuts. They lead off every newscast with the story (what Iraqi referendum? what fascistic special election?), refer to the victim exclusively as “Pam,” keep reminding us of the money factor by endlessly re-running chopper footage of the Xanaduesque hilltop mansion that the couple was building, bring on FBI profilers whom they then machine-gun with leading, lurid questions (“Does the fact that Pam was in her T-shirt and panties indicate that she knew her attacker well?”), and otherwise openly flirt with the line between showing proper sympathy for a grieving husband and accusing the bastard of outright murder. I’ll probably never mention this case again, but just know that for the next year or so I’ll be banging my head against the wall whenever I stumble across the 10:00 news.

I don’t mean to jinx the man…

October 3, 2005…but tonight I felt a real rush of sadness that Robert Altman just can’t be with us that much longer.

Scales of Justice

September 24, 2005There’s a little advertisement for a bail bond company that shows up on late night broadcasts of Jerry Springer and Cheaters which is so cheesy, both morally and aesthetically, that I feel rather happy whenever it comes on. It follows a doltish looking white guy who lip-synchs a cheap rap ditty as he’s being busted, booked, and then bailed out of jail, and ends with him arriving back at home where his mother is waiting for him, only “Mom” is a mustachioed black man done up in drag. (Whether this is meant as some jokey allusion to the actual penitentiary experience, I don’t know.) I’ve never managed to notice the company’s name because the whole thing throws my mental gyroscope too far off its axis, but the ads for another company, Aladdin Bail Bonds, emphasize just how serene the whole Gettin’ Busted experience can be. Their most memorable effort begins with an attractive, wholesome looking blonde—why, it could be you, missy—being rousted from her slumber by a ringing telephone and then crying out, “Ar-REST-ed!?” (Ma’am, may I ask just who it was you thought you were married to this whole time?) Cut to the Aladdin offices, where some bail-bondsman cum New Age guru brings the distraught woman a glass of water (aww…) and touches her comfortingly about the shoulder before shooing her off to bail Clyde Barrow out of the pokey. All of these ads treat the criminal act with the same non-accusatory indifference with which insurance companies view cyclones and hurricanes; in fact, they’re so impartial and highminded that their creative director probably deserves Rehnquist’s chair. Aladdin’s slogan—“We get you out. We get you through it.”—is the perfect enabler’s motto, glossing over as it does the traumas that grease its wheels. In their view it’s a given that your husband or son will be arrested someday, whether it’s for jaywalking or attempted murder who’s to say, and there’s no point in wondering how things came to such a pass. Bailing the hubby out of jail in the dead of night is just one of life’s grubby little chores, like cleaning up after the dog, that’s handled quite easily if you just bend your mind the right way.

Like a Hurricane

September 13, 2005So in the space of two weeks Mother Nature has accomplished what the war in Iraq couldn’t do in two and a half years: first, forced George W. Bush to admit that he’s less than perfect, and then forced one of his staffers to pay the price for his mistakes. FEMA chief and personification of cronyism Mike Brown walked the plank yesterday, and whether or not he was forced to do it at sword-point, he delivered one last maudlin gust of the misdirected reasoning that’s made his name an international byword for incompetence. Insisting one last time that he’s been scapegoated by the media (but not by the president), he said, “The press was too focused on what did we do, what didn’t we do, the whole blame game. I wanted to take that factor out of the equation, so that the people at FEMA, who are some of the most hard-working, dedicated civil servants I have ever met, could just go do their job.” (See, he’s not just some historical footnote—he’s a martyr.) But it doesn’t take a Plato to suss this one out—the press was only doing its job when it “focused” on Brown’s appalling shortcomings, and it was clearly Bush who cut Brown’s legs off and then left him swinging in the winds of history. (Brown was unharnessed from his hurricane duties four days ago to decrease his visibility, after which that jerk Scott McClellan refused to give him a vote of confidence even when the reporters howled for one).

If not for the damage he’s caused Brown would be remembered as a two-bit resumé padder, and even with it I suspect it’ll take some googling a year from now to recall who the hell he was. But Hurricane Katrina has accomplished things even more remarkable than making Bush flinch. For one thing, a poll last week showed that 44% of the country was “ashamed” of the government’s response to the disaster. That’s right—ashamed. This, in a country where the biggest insult one person can lay on another is, “You don’t have any self-esteem,” where France and Germany are regularly hooted at for their effete and timid morality, and where the mantle of self-entitlement weighs so heavy on us that we continue gobbling up fossil fuels and our grandchildren’s capital without a second thought. Bush’s ratings have taken a further beating, with only 39% of the voters giving him a thumb’s up, as the man himself has looked hard-pressed to explain his own response to the storm. The largest issues of our day—the federal government’s responsibility for its citizens, the roles that race and class play in American society—are getting a more serious hearing in the media than they’ve had in years, and twice now on major network news shows I’ve heard the word “property” pronounced with a nearly Marxist disdain. We suddenly have our heads cocked quizzically to the side and one ear raised like dogs watching their masters do something funny. We’re almost cute in that position, for sure a lot cuter than the supine position we usually adopt in the face of the White House’s antics, and all it took was the trashing of one of America’s great romantic jewels. It’s happened here, in our backyard, and the people we see struggling in the muck look unmistakably like ourselves. The Department of Homeland Security has been exposed as a hive of grifters and incompetents, Bush’s take-charge reputation is in shreds, and for once Karl Rove can’t control the camera angles or redirect the anger. Whatever Katrina did to New Orleans, it’s done even more to America, something that Richard Clarke, Cindy Sheehan, and 1,800 ghosts working full-time couldn’t do. Even if the furor dies down before the World Series begins, it’s a breath of fresh air in the meantime.

The eye of Katrina, before landfall:

September 8, 2005

This Poor Cracker’s Land

September 7, 2005

…and…nothing, I guess. I stopped writing on that last post, feeling too dispirited to go on, and it turns out it was just as well. Virtually everyone I know who’s blogged about Katrina, and a lot of people who don’t blog at all, saw New Orleans the same way I did, as a giant brackish Petri dish where Social Darwinism, supply-side economics, and Compassionate Conservatism are finally free to breed with each other. Talk about your toxic soups. At least we know now why Republicans think that Big Government just messes things up—it’s because it does when it isn’t accompanied by a little thoughtfulness and compassion, which are not these people’s long suits. No one’s captured the nightmare of Bush’s America better than my friend Dana Knowles when she said, “Living under BushCo is like being trapped inside a Ponzi scheme run by the Manson Family.”

Now, if you’ve never seen this cocksucker Scott McClellan, today he bullshitted his way through another White House press briefing, parroting the operative Talking Point over and over again: “Now’s the time to help people, not play the Blame Game.” The Blame Game! See, it’s all just tiresome partisan politics, people trying to nitpick this president so he can’t get it on with his compassion! In different conditions I might agree, but not here, not with this crowd, because George W. Bush and his friends live in a Never-Neverland of eternally deferred accountability. They know if they stonewall long enough people will either stop caring, lose track of the details and chronology, or both. (The White House has already floated the idea that the feds couldn’t move without a state of emergency being declared. The amazingly few non-amnesiac members of the press quickly noted that Blanco—and Bush himself—had done exactly that the night before Katrina made landfall.) I’d love to hear what the reporters say to McClellan when they get a couple drinks in them, even if I suspect McClellan knows better than to drink too much around them. McClellan is a Frankenstein stitched together from pathetic qualities, but the most pathetic of them all might be his “affable” way of occasionally acknowledging his adversarial relationship with the press with statements like, “I like and respect you all, and I don’t take it personally.” Well, not even Scott McClellan is so goddam stupid that he can’t see that the tone and implications of the press corps’ questions, at least on the days it does its job, are a spit in the face to whatever shred of personal integrity he thinks is still clinging to him. You can practically see Karl Rove winding up the crank in McClellan’s side just before each briefing, and his status as a tool is so apparent that his greatest qualification for the job is that he doesn’t seem to mind that fact. If he had an ounce of self-respect he’d be challenging Bush and Rove to a duel with pistols at dawn.

As usual the administration is talking out of both sides of its mouth at the same time. Just as McClellan is busy decrying the Blame Game, nearly everyone else is busy pointing fingers: at the locals who didn’t evacuate, at the (Democratic) governor and the (Democratic) mayor, at the (probably Democratic) looters, at all that gosh-darned water that came in with the hurricane (who’d a thunk it?), and at those reliable old stand-bys “red-tape” and “bureaucracy.” An interesting sidebar to the whole mess is the Name Game: what to call the victims. Last week most news reports were calling them “refugees,” and around Saturday, having scoured every other website, I happened to look at Limbaugh’s to see what Fathead had to say about the mess. It was surprisingly little, but his home page did contain a headline reading “These People Aren’t Refugees” and a link that took you to a Merriam-Webster page defining “refugee” as “a person who flees to a foreign country or power to escape danger or persecution.” Okay, fine, I thought, if for whatever arcane reason Rush doesn’t want to call these people who’ve suddenly been made homeless and transported to aid shelters in other states “refugees,” then I’ll just avoid that word in his tender presence. It turns out, though, that many of the victims themselves are balking at the word, preferring instead “American citizen,” “survivor,” or even the white-paperish term “evacuee.” Any of these do lack a couple subtle insidious connotations that give them the edge, I guess, as they carry neither the depth of powerlessness nor the seeming permanence of “refugee.” On the one hand it’s just another indication of how much importance people place on language, even in times when you’d think such fine distinctions would be the farthest thing from their minds; on the other hand, we should probably be elated if this is Limbaugh’s greatest insight into the whole fiasco.

The mainstream media is getting back to normal after the stress and trauma of doing its job last week. When some reporters asked George Senior a couple days ago about the criticism of Numbnuts, he said, “Well, if you repeat it to Barb you better wear a flak-jacket,” and the press corps hooted with laughter right on cue, as if she really is just Irene Ryan in pearls instead of some backwater Lady Macbeth. (Senior then went on to compare the criticism to the Monday morning fallout after a losing football game. The apple didn’t fall six inches off this tree.) From here it looks like the media loves Hurricane Katrina. With Bush’s negative poll numbers and the “great visuals” of human suffering in hand, they’re feeling a little reckless and can be seen striking skeptical, angry postures they never dreamed of taking post-9/11—you know, when it might’ve done some real good. They take time out from that yummy footage of ballooning corpses bobbing in the floodwater to recount the latest zingers flying back and forth between the state and feds, but it feels less like an exercise in democratic illumination than someone swinging a stick in a big circle and whacking two hornets’ nests at the same time. At least BBC is relishing the administration’s discomfort for truly political, not Nielsen-driven, reasons. Their raw footage and blunt narration is strikingly devoid of American news’ “balanced” dithering, or what Al Swearengen would call “this several hands fucking shit.” As the camera zooms in on a pile of debris, topped by one of the pathetic HELP signs, still littering the Convention Center, the British reporter flatly declares: “It’s a monument of shame.”

Katrina, Katrina

September 3, 2005· Survivors living among corpses

· FEMA head: Working in “conditions of urban warfare”

· Armed gangs attempting rapes, police warn

· Bodies dragged into corners at convention center

· Sniper fire halts hospital evacuation

That’s the slate of subheadlines that could be found at CNN.com two nights ago. I include them here not because it still seems unreal that the location in question is New Orleans, Louisiana, but because seeing them grouped together like that—from before the first convoy of relief trucks rolled in, causing the resulting gasps of relief to be mistaken for “cheers”—does a good job of showing just how ugly this thing got. That’s important because in an about-face the Bush administration had chosen to answer the accusations of incompetence and insensitivity with a limited modified hangout, rather than the straight-ahead stonewalling it normally prefers. Bush has offered a couple of mea culpas in the last 24 hours, but they’ve been watered-down generalities (e.g., the relief effort was “not acceptable”) that identified neither specific shortcomings nor (most importantly) who was responsible for them. But that’s Bush’s way. Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert had to issue a clarification for floating the idea of bulldozing instead of rebuilding the city. Not so FEMA head Michael Brown, though, who suggested that those haggard people clinging to life on chunks of shattered Interstate highway wouldn’t have anything to complain about if they’d just gotten their asses out of town when they were told to. Despite being fired from his previous job as the head of the International Arabian Horse Association (what’s the emoticon for throwing one’s hands up in the air?), and despite his supremely fucked-up job on Katrina, Bush gave “Brownie” a very public atta-boy yesterday.

America is a country famously uninterested in history. Oh, we like to watch grainy footage of German artillery corps blasting their way across the Russian steppes, and we like to make grand, meaningless comparisons when they serve our purpose (indeed, one of the duties distracting Bush from Katrina the day after she made landfall was a speech likening the Iraq war to World War II), but when it comes it to actually observing the results of some past occurrence, deriving a lesson from it, and then retaining that thought long enough to base some future decision upon it—well, forget it. More and more we live in a nebulous haze where things just happen. The President makes some bold statements. We invade a foreign country. The President’s statements turn out to be lies. We reelect him. Now a hurricane blows in. People suffer. The President mumbles some shit. Life goes on. The subtly anesthetizing quality of American life can make it hard to remember what it was that pissed us off a year ago (while writing something about the war a couple of days ago, I had to Google “nicholas + beheading” because I couldn’t remember Nicholas Berg’s name), and even within a week’s worth of 24-hour news-cycles, developments that were amazing on Tuesday can seem ho-hum by Friday.

But what’s going on in New Orleans is a genuinely big deal—or should be. That qualification is necessary, of course, since all the wrong things become big deals in America. The Rodney King riots, which should’ve touched off a moratorium on all human activity in the United States until we figured out some way for the people who just happened to be born black and white to coexist without freaking the fuck out over everything, were instead dropped like a hot potato; after all, it was an election year, and after Bush and Clinton each did a quickie goggle-eyed tour of South Central, they got the hell out of there and didn’t mention race again for the rest of the campaign. The Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill hearings, instead of fostering much sincere or thoughtful analysis about gender issues, turned into political football, with both sides’ cheerleaders overlooking the weaknesses of their own arguments and witnesses in their eagerness to pummel the others’. (Far more objectionable than the pubic-hair joke—I mean, come on already—was Thomas’ ludicrously transparent lie that he’d never discussed Roe v. Wade in law school.)

New Orleans is also being talked about in terms of race and property, as well it fucking should be, but it offered something more: It offered a vision of the way of life we’ll have if we don’t stop thinking of Big Government as an obscenity. Ever since Reagan first claimed the Republican nomination in ’80, we’ve been backsliding in a way that’s eventually going to kill us, city by city, if we don’t put the brakes on. I must’ve heard a hundred commentators compare the scenes in New Orleans to a Third World country—the city’s French colonial architecture summons up mental pictures of Haiti, in particular—and