The last few days I’ve been following—well, at least as far as my stomach will allow it—the “national debate” about whether the rightwing’s protests against Obama are racially motivated. The discussion has grown somewhat blurry because one of the things kicking it off—Rep. Joe Wilson’s shouting “You lie!” during Obama’s healthcare address to Congress—also helped to ignite a separate but equal debate about the loss of civility in society. Of course we could have had that debate at any time since the first Vince Foster rumor started flying around, but what the hell—better late than never.

One comment in the racial “debate” (read: “media-generated doo-da”) did make me do a mental double-take. It was delivered during one of The Lehrer News Hour’s drowsy-making roundtables in which a handful of scholars and wonks work overtime to cancel each other out. One of the panelists (most of whom were black, if it matters) opined that the current debate is not racially motivated because none of the markers he’d expect to see in such a case—a lot of noise about affirmative action, f’rinstance—are actually present in it. This begs the question, of course, that Obama, drawing fire from all quarters for his activities on any number of other political fronts, has barely said boo about affirmative action since announcing his candidacy for the White House. It also ignores the fact that racial markers can be seen in debates where they don’t belong, a perfect example being the phony siren call that Obama’s plan will provide healthcare to illegal immigrants—which, of course, was the very point under discussion when the clock began running on Joe Wilson’s 15 minutes of fame.

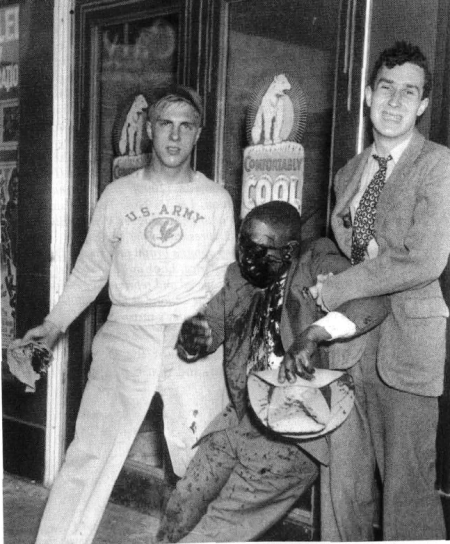

In any case, the current round of iffy behavior only builds upon the last round of iffy behavior—that series of racially skuzzy emails and tweets that magically emanated from only Republican congressmen—and on backwards to such savory treats as the “Obama foodstamp” which appeared during the presidential campaign. Things don’t happen in a vacuum, we’re always told, and in this case I believe it.

That News Hour segment did provide its viewers a glimpse of that sorry picture of Obama in witch-doctor drag, a work which absolutely tortures the concept of “plausible deniability.” (That phrase may be musty but it never seems to lose any relevance.) Of course it wouldn’t matter a whit if it was Marcus Welby, M.D. who had a bone stuck through his nose—such a picture would still have a racial component thanks simply to America’s complicated history when it comes to blacks, to Africa, and to Third World societies in general. Some things just aren’t possible in White America, such as the idea that we can dress up cartoon figures in, say, sombreros and serapes, and make them funny-talking people who only want to take a siesta, without it echoing all of our historical biases against Mexicans. And, of course, it isn’t Marcus Welby in the witch-doctor picture, but a sitting U.S. president who, as the saying goes, “just happens to be” an African-American. In what may be the most damning fact of all, none of the picture’s admirers seem to mind that a witch-doctor is off-center as an expression of their ostensible criticism of Obama’s policies. The rightwing’s primary complaint against “ObamaCare” has had little to do with medical acumen; it’s mainly revolved around the bogeyman’s plan to enslave America by taxing our asses to death for generations to come. Given the chance to forego the racist baggage and pick a symbol which actually addressed their stated concerns, they decided instead to shame their children and go with the witch-doctor, all for the sake of a cheap cracker laugh.

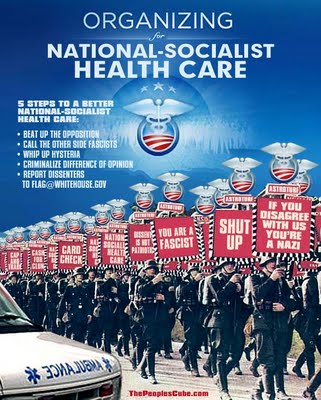

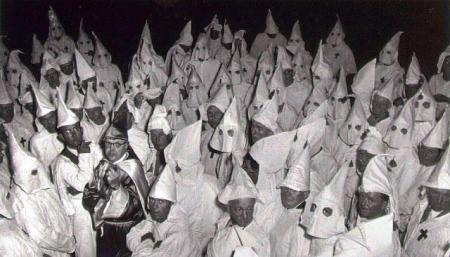

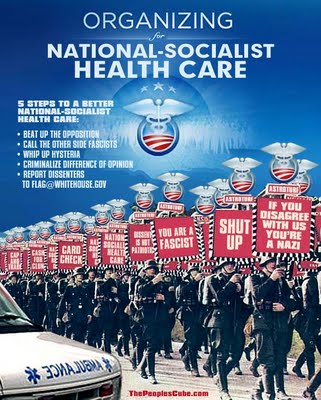

The vision of Obama as totalitarian golem can’t get any lower than it does in the various drawings, posters, flyers, etc., that depict him as a modern-day Hitler. Do you really think there’s no racial component in those works just because Hitler was Caucasian? (Not that we claim the dude with any pride.) The second most visible historical figure on anti-Obama literature is Osama bin Laden, and whenever Adolf or Osama need a break—this political allusion stuff is hard work!—yet another mass-murdering anti-Semite, Uncle Joe Stalin, is ready to step in and spell them. If the rightwing’s objections to Obama center around his tax policies, then why all these comparisons to history’s worst monsters? Why overreach and garble your own message? Exactly which group is it that Obama has targeted for scapegoating and murder? If you start out by comparing tax-and-spenders to Adolf Hitler, who can you use as a panic-button if a dictator bent on genocide actually comes along?

All of this makes sense if we just remember the whisper campaign—or rather, the stage-whisper campaign—about Obama being a closet jihadist. The Hitler posters aren’t intended to reference the Third Reich’s economic policies in any meaningful way; their only point is that Obama, somehow, for some reason, wants to “destroy America.” They play on all the what-if rumors of his secret birth in Kenya and the notion that, as an agent for radical Islam, he’s the best positioned Fifth Columnist in the history of espionage. Boo! Unsurprisingly, these jackass hallucinations fit hand in glove with the more artfully phrased dementia issuing from the Kristols and the Kagans of this world, folks who are glad to exchange support with any dimwit quarter, even if it’s Princess Chuckles of Wasilla and her nutty rants about “death panels.” Invoking the Hitler-Stalin-bin Laden triad really makes no sense when you consider what other historical models are available out there. You don’t need to be Will Durant to think of King George III, Mr. No-Taxation-Without-Representation himself, and a figure who left a Sasquatch-sized footprint on our national identity. It’d be pretty hard for liberals to yell “Racist!” about a picture of an overfed Obama draped in ermine and sporting a powdered wig (they might even find it funny), and as a protest against his tax policies it hits the bull’s eye without the overkill Holocaust vibes. But expressing himself in a cogent, proportionate way is almost always a low priority to the rightwinger, who’s usually most concerned with feeding his cherished sense of victimhood no matter how destructive the results are.

At least the wingnuts’ artwork is more polished than it’s ever been, consisting as it does of a lot of Photoshopped propaganda posters. Socialist Realism was an eye-catching art form if ever there was one, but today’s crop of work is just a little too ugly, a little too raw and stupid, to inspire anything other than revulsion right now. Someday I hope to view it with the distanced and bemused incredulity evoked by the old “Loose Lips Sink Ships” posters of World War II, but that day isn’t here yet. It can’t get here soon enough.